A Concise History of AEC Data – Part 1: The Analogue Era

History of AEC Data

In the past few years, there’s been a lot of talk about data – whether is be the famous ‘big data’ buzz work, data privacy, or machine learning – there’s no denying we live in the era of data. Each of us generates more data than ever before in history and equally, has at their fingertips more data available than ever before. Data is a fundamentally powerful thing – it gives insights that drive decision-making. One of the most famous early examples of data driving insight and having impact is the case of John Snow’s cholera outbreak maps.

Given data’s fundamentally powerful nature, it is surprising that in the creation of the built environment, we talk about it so seldom. We’re in the business of creating complex things in the real world. Let’s be clear – for the purposes of this series, when we speak of data, we’re talking about the data the represents ‘thing’ before someone comes along and creates the physical manifestation of that ‘thing’. This ‘thing’ could be a road, building, bridge, water treatment facility, sewer system, ductwork, mullion, cable tray, counter top or any other physical object in the built environment. Where do these ‘things’ exist before they physically exist? Broadly speaking, before any of these exist in the physical world, they exist as data, in some way shape or form. As stated by Mario Carpo in The Alphabet and the Algorithm:

“…architectural design is a purely informational operation….”

I would say more generically that any design is an operation that is purely an exercise in information or data.

If you do hear data talked about in the AEC industry, it is normally framed in the context of “Data Exchange Standards” or BIM (Building Information Modelling). Yet as we’ve previously discussed in other posts, when BIM is talked about, usually it a discussion of software such as Revit, Tekla, or ArchiCAD, not data. However, as will be discussed in further detail in this series, these discussions normally boil down to software issues, more than they do fundamental data issues.

A key skill of a computational engineer is lateral thinking and the ability to break a problem down into its fundamental atoms. This skill applies not only to a computational engineer’s discipline-specific expertise, but also, to their approach to coding. Computational Engineering in the built environment can be thought of as engineers who can code. Coding is a means to manage, create, and get use out of data. Fundamentally, the design, creation, and maintenance of the built environment relies on expertise that lies across many different disciplines. The common thread that ties all these experts together is data. Therefore, it is critical to think of data agnostically to any particular software when thinking of the AEC industry.

In this 3-part series, we will explore the history of AEC data and show how the designers of the built environment have used data over the millenia to portray designs. There are three main era’s of data that we will explore:

- Analogue Era (100,000BCE – 1990’s)

- Digital Era Part 1 (1990’s – 2000’s)

- Digital Era Part 2 (2000’s – Present)

We want to ask for every era some critical questions:

- What was the data that represented the thing before it existed?

- Who was responsible for the creation of this data?

- How was data transmitted to the hands that ultimately created the built environment?

These three questions will allow us to fully understand where we as an industry have come from and therefore contextualize any conversations about data for the future.

We’ll start with the Analogue era, which has spanned unsurprisingly for the majority of human history. Of these 100,000 years however, data’s story has three main chapters

- The Neolithic Builder

- The Master Builder

- The Building Drawer 1.0

As implied by the title, this is a brief history at best and each era had overlap with other eras. The key here is that we understand in its purest form the key difference of the data that was created, handled, and used to create the built environment for each era.

The Analogue Era

10,000 YEARS AGO – The Neolithic Builder: Make the thing out of necessity

In the beginning, our species didn’t have a ‘built’ environment, we just had the environment. Neanderthals lived in caves or other abodes crafted by nature.

The first known examples of built environment were around the 10,000 years ago with humans making simple structures out of stone. What was the data used to make these first attempts at the built environment? The data was human experience. First was the experience of sleeping in the bare elements one realizing “Hey, it’s colder when I’m not surround by other material. I need to find some sort of cave to sleep in”. Eventually, after realizing this, somebody thought “Wow, how great would it be if we could make our own cave and surround ourselves with material that protects us like the cave does?”. Certainly, this previous experience was all the data early humans had at their disposal. From there, they could go and experiment with stacking stones for instance to make their own artificial caves. Again, the data on how to do this was completely experienced-based. It was trial and error mixed with a lifetime of experience with gravity that would eventually lead to a pile of stone that represented the first built environment for our species.

- Data: Human experience – stored in a human’s brain

- Who Generated the data: Human who wanted the structure

- How was data transmitted to reality: Direct brain to hand neuron link from the brain of the human who wanted the structure to their hands.

1,000 YEARS AGO – The Master Builder: Model the Thing on a Small Scale

Let’s fast forward a few millennia. We are starting to settle in the first cities which feature permanent roads, bridges, running water and sanitary systems. The built environment is getting more complicated and meant to serve many generations. Society is further developed and calories became more abundant, people began to take on the first forms of specialization. In order to create these more complicated environments, society has a need for people who can understand how to make all of these relatively complex systems. The name of this person is the Master Builder – a scholar and ‘jack of all trades’ expert in architecture, engineering, and construction. The pyramids of Egypt, the Roman road system, and the Greek Parthenon all were products of this chapter of data history in the built environment.

The idea of the Master builder is epitomized by the fabled story of Brunelleschi’s turnip whereby Brunelleschi was the only who who knew the final design of the building and was on the construction site daily, constantly instructing the workers on what to do next in order to make his vision into a reality. Obviously, in order to create anything physical, using words to describe it is quite difficult (Have you ever tried describing what someone looks like over the phone? Not exactly a great way of painting a Mona Lisa for people). So for things that were a bit difficult to explain with words, Brunelleschi would use physical models to describe what his intent was, such as quickly carving a turnip into the shape of what needed to be created, most likely only creating enough information to get the workers through what they needed to build that day. The memory storage device of a turnip could only show so much at once after all.

- Data: Experience and Training of Master Builder verbalized and/or made into a small scale physical object which represented the desired object or part of the desired object

- Who generated the data: The master builder

- How was data transmitted to reality: Constant conversation between the master builder and the hands that made the final product

600 Years Ago – The Building Drawer 1.0: Draw a Picture of the Thing (on paper)

Around the 1400’s, Alberti came along and took us from the master builder era to industry as we know it now. He separated the powers of architects, engineers, and construction practitioners, although at first these disciplines were still quite interlinked as seen in the cases of great designers which dabbled on all sides of this spectrum such as Guastavino, Dieste, Isler, and others. In any case, around this time, the mathematics of perspective and orthogonal views were perfected enough to create a common vernacular for how to represent the built environments on paper, thus creating a system to portray our 3D world in 2D. These early drawings (blueprints they could be called) were a step in a direction which would allow for the storage and spread of data for the creation of the built environment. After all, its much easier to copy and transmit paper drawings rather than a bunch of Brunelleshci’s turnip models, which would be hard to copy accurately and store for long periods of time. The key change for this era is as opposed to the person with the idea for the thing verbalizing and/or making props to portray their idea to the people constructing the thing, the person with the idea for the thing poured all of their instructions onto a pieces of paper. This paper, covered in the marks of the designers, in theory contained all the data of the building, which in turn could be translated to reality by the people responsible for copying that vision into a reality. It is interesting the quote from Sutherland that drawings were nothing more than “….dirty marks on paper” [1] in the context of this conversation. Not to be demeaning, but it’s important to realize that in essence, that’s the data in this era was just that – marks on paper.

This tradition continued and matured well into the 20th century, bringing us much closer to the AEC industry we know today with its contract structure which silo’s architects, engineers, and contractor’s responsibilities.

- Data: Architect/Engineer’s “….dirty marks on paper”

- Who generated the data: The Master Builder/Architects/Engineers/Draftsmen

- How was data transmitted to reality: Giving drawings over to construction people to copy into reality

Summary

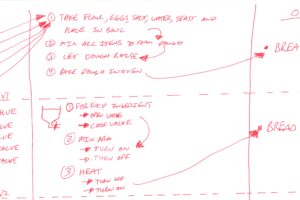

The figure above shows a summary of these three chapters of the history of AEC Data and in the built environment. It is important to note another key change that started during this third chapter of the analogue era. In parallel with this trend to store data on paper, the world grew more complex – namely, the invention and proliferation of electricity into our lives took buildings into a new domain of complexity as now they were not just brick and mortar structures, but rather, collections of serviced spaces which needed the input of a new breed of expertise in the building services engineer. Again, these changes happen gradually and didn’t necessarily change the type of data that was being transmitted or where it was stored (still just marks on paper), but rather, it increased the amount of data needed to describe the built environment before it was built. The amount of data was solely multiplied by increasing the number of parties needed for the creation of the built environment. However, in the next era, not only will be we an increase in the number of parties, but also, and increase in the rate at which all parties can create and transmit data.

[1] Sutherland, “Structure in Drawing and the Hidden-Surface Problem.” 1975